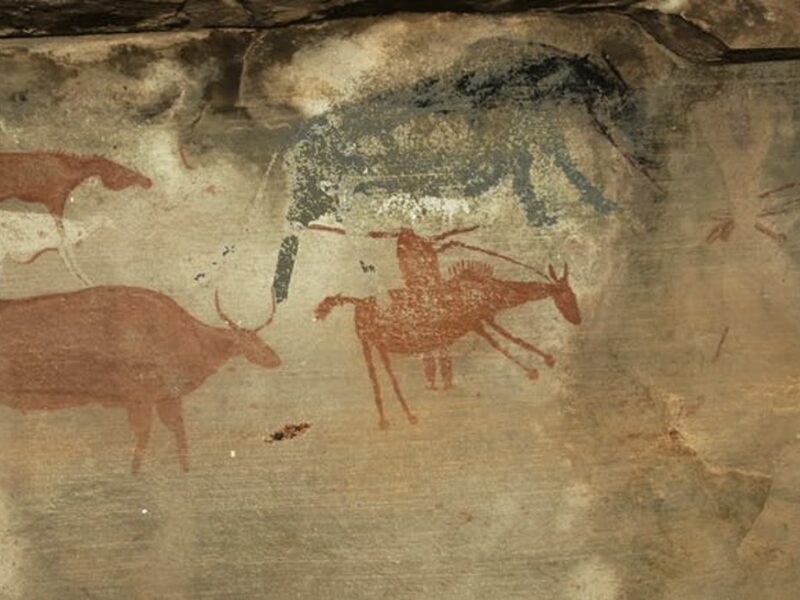

The rock art of bandit groups is bound up with beliefs in the ability to call upon the protection of the supernatural. Baboons and ostriches, painted with images of livestock and people on horseback with firearms, were heralded for their associated powers pertaining to escape and protection while raiding. For these runaway slaves, rock art was one of several crucial ritual observances performed to prevent the likelihood of ever returning to a life of oppression.

AuthorSam Challis

Sam Challis is Head and Senior Researcher at the Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand.

His focus is on the interaction between hunter-gatherers, pastoralists and farmers, as well as Europeans, as expressed in rock art around the world. His DPhil focused on the acquisition of horses by creolized raider groups in the nineteenth-century, and his research programme in the mountains of Matatiele in the Eastern Cape, aims to redress the imbalance of this neglected former-apartheid region while training local community Field Technicians.