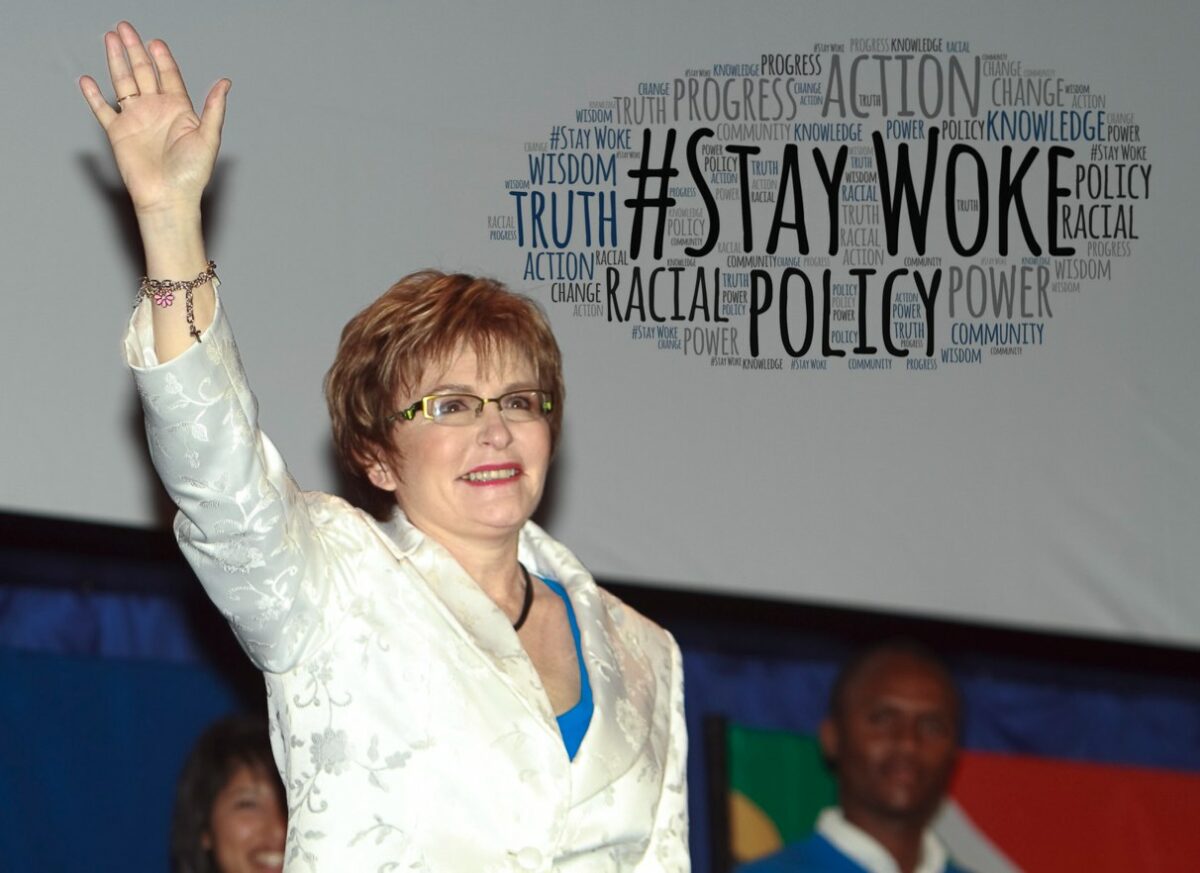

In a discussion with Professor Hussein Solomon of the University of the Free State’s Department of Political Studies and Governance, South African politician Ms. Helen Zille conceptualized and unpacked the popular notion of “wokeness”, which is labelled as ‘Critical Theory’ in academic circles. She explained how the theory infuses the academic traditions of Marxism and Post-Modernism. At its core, wokeness is “inverting society’s conventional hierarchy of privilege in order to promote marganalised identities.” It is a struggle based on inborn attributes of personal identity such as race, sex, sexuality, gender and disability. It explains why intersectionality features often in universities’ Post-Modern references.

While the international community is aware of the cultural wars being waged in America, this is largely ignored in the South African context. Ms. Zille identified wokeness as a threat to the country’s Constitutional Democracy, especially when culture is a mere replication of the latest trends in America and Britain and ignores South African complexities. Unlike America, South Africa does not have deep-rooted institutions built over centuries that seek to protect individual rights and a culture of democracy, but fragile emerging democratic institutions that may not be able to survive the wave of wokeness. In discussion, Ms. Zille explains why the “properly woke’s” request to have separate graduations for African students in South Africa cannot work and how the country’s Constitution promotes the inclusion of all.

In her book, Ms. Zille further seeks understand how wokeness, which is supposed to promote inclusion, has begun symbolizing extreme intolerance and how it is utilized as a tool to enable a “cancel culture”. The movement is now used to tear down statues, deface paintings and monitor others’ speech ‘infringements’ to ensure conformity. Instead of engaging in rational debate regarding their dissenting views, online communities silence those with different opinions. This poses a setback for social progress.

Wokeness argues that oppression based on biological and cultural identity is the root of societal inequality, and that knowledge should be (decolonized) stripped of the methods and content used in Western society in order to achieve social justice. In addition to this, the woke believe that society consists of power hierarchies that determine what should and should not be known, as well as how events and actions should be interpreted. They believe that its is up to Critical Social Justice activist to expose these unequal power relations and dismantle them. It is worth mentioning that unequal power relations include racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, fatphobia, ableism and other prejudices. Finally, they seek a hierarchy free society.

Ms. Zille’s page-turner proved to be informative, a little controversial for some, but a definite must-read. Most interesting were her examples of wokeness in the country and the chapter explaining why wokeness won’t work in the South African context.

Ms. Zille’s discussion ended on a hopeful and optimistic note. She remains hopeful for the country as its citizens “are intelligent enough, sensible enough, ethical enough and rational enough” to assist it in achieving its potential.