“I am an African. I owe my being to the hills and the valleys, the mountains and the glades, the rivers, the deserts, the trees, the flowers, the seas and the ever-changing seasons that define the face of our native land”- Thabo Mbeki

Twenty-five years ago, former President Thabo Mbeki gave one of the most iconic speeches in the history of the Republic of South Africa, titled “I am an African”. The words from his speech resonated in the hearts of his fellow countrymen. It captured the essence of an assertive African identity and gave hope to many at a time when The Economist had just dubbed Africa The Hopeless Continent.

The timing was ideal for the ruling African National Congress (ANC) as it sought to renew the country’s image and reintegrate itself into the global community.

South Africa’s new Constitution – a beacon of human rights

Under President Nelson Mandela’s leadership, the country’s foreign policy was characterized by human rights; respect for justice and international law; the advancement of African interest; multilateralism; as well as regional and global economic co-operation. Soon, the country’s values stretched far beyond its’ borders.

Nelson Mandela’s government was committed towards a human-rights based foreign policy and expressed solidarity with those oppressed abroad, in recognition that the ANC requested global support during apartheid. This optimism died quickly and has become a distant recollection.

South Africa’s democratic and human rights tale has become one of woe. The country has received global criticism for its’ perceived failure to actively condemn human rights abuses around the globe. Presidents Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma chose to practice realpolitik. They chose to back political elites instead of people and embraced “Southern” solidarity themes. Over time the country’s commitment to human rights eroded as Pretoria proved unwilling to confront authoritarian governments and human rights abusers in Sudan, Zimbabwe, Myanmar, China, Russia, and North Korea.

Ramaphosa’s challenge to re-orient foreign policy

When Cyril Ramaphosa took office, optimists considered him to be less likely to support authoritarian regimes, as he was not in exile and had not enjoyed their hospitality. This was not to be the case. Ramaphosa’s narrow win in December 2017 at NASREC, denied him the ability to re-orient the country’s foreign policy. Compromise and continuity were the watchwords as he sought to consolidate his power base within the ANC. In addition to this, he needed to preserve the country’s standing with multilateral forums such as the African Union (AU), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the BRICS forum. Some believe that his being tasked with reconstructing the economy and delivering jobs and better wages for the country’s citizens, did not go well with the pursuit of ethical foreign leadership.

Consider here the members of BRICS. Populist Bolsonaro has not only botched his country’s COVID-19 vaccination roll-out but also undermined Brazilian democracy. Modi is increasingly pivoting India away from being a secular democracy into a Hindu nationalist state which is bringing on greater sectarian strife. Putin and Xi, meanwhile are authoritarian to the core, to which Alex Navalny and the Muslim citizens of Xinjiang could testify. Yet these countries are major powers globally, and human rights considerations had to be put aside in pursuit of national interests. Ramaphosa’s promise of a “New Dawn” therefore never entered the foreign policy realm.

Ramaphosa’s foreign policy has taken a more pragmatic approach and is consistent with the country’s traditional non-alignment approach. While it is more pragmatic, it is still a long way from that of President Nelson Mandela. It lacks coherence and coordination. It lacks clarity, definable goals and objectives. While it seeks to return to the African Renaissance and put African interest first, these objectives cannot be achieved without adequate interest, resources and inter-departmental co-ordination on multilateral issues and institutions. The insufficient budget allocations and related mismanagement of departmental funds in the country’s diplomatic and consular missions does not help either. The limited availability of appropriate human resources aggravates the situation even more.

South Africa’s foreign policies and friends – what does it mean for women’s rights?

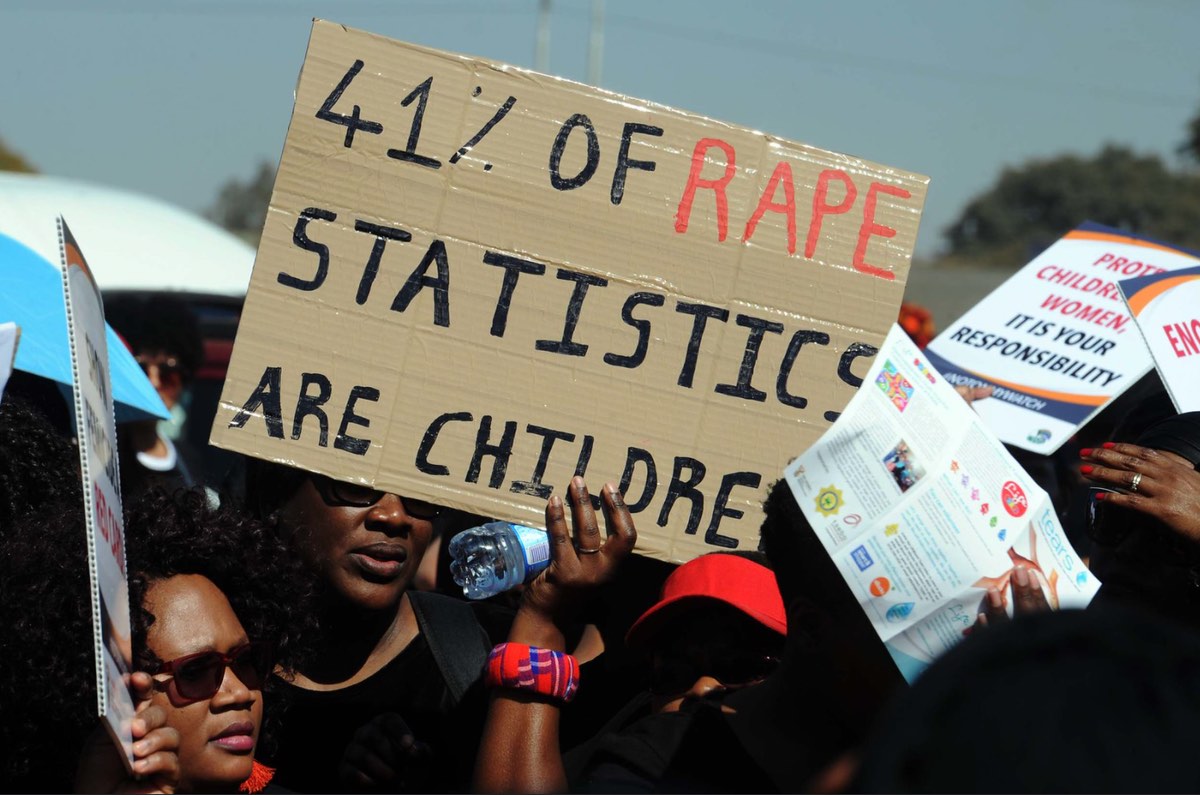

South Africa’s lack of commitment towards human rights in its foreign policy reflects its internal situation. South Africa is often referred to as “the destination of femicide”. Over 2,700 women, and 1000 children, were killed as a result of gender-based violence according to the 2019 crime statistics. During the first three weeks of the 2020 lockdown the country’s Gender Based Violence and Femicide Command Centre recorded over 120,000 victims. Prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, femicide in the country was five times higher than the global average, while the female interpersonal violence death was the 4th highest out of 183 countries in 2016. Between 2019 and 2020 the country had an average of 146 sexual offences and 166 rape cases per day.

It is noted with interest that the country’s ‘friends’ have their human rights challenges.

Iran

Human rights violations in Iran, for example, have become more dreadful and appalling. Since 1979 women’s bodies became the main battlefield for ideological wars. Two weeks after the Islamic Revolution the “Family Protection Act” which made the minimum age for marriage 18, was cancelled and wearing the veil became mandatory. This triggered protest which resulted in Khomeini’s supporters attacking unveiled women. Women are subject to entrenched discrimination and violence in the country. A woman’s life regarded as half as valuable than that of a man and in a court of law, her testimony is viewed less credible (half as credible) than that of a man.

Women are obligated to sexually fulfill their husband’s needs or lose their maintenance payments, shelter, food and clothes. Girls and women are subject to physical punishment or be killed by a male family member if they “dishonor” their family. According to Human Rights Watch the Ayatollah Khomeini has described the notion of gender equity as unacceptable to the Islamic Republic.

Yemen

In Yemen, women experience deeply entrenched gender inequality which is based in a patriarchal society with rigid gender roles. The country has negative gender stereotypes of women, a discriminatory legal system and economic inequality. Regardless of the dire economic crisis, damaged infrastructure and collapsed services, women are expected to provide food and care in their homes. Women are subject to sexual and physical violence in the absence of male relatives.

Democratic Republic of Congo

Women and girls in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo face the constant threat of rape, as sexual violence is used as a weapon to control, humiliate and intimidate women. The breakdown of social norms and the destabilization of society in the area has contributed towards rape becoming endemic in the region. Perpetrators go unpunished and justice is beyond reach for the victims.

Saudi Arabia

In the latter half of 2019, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia Prince Mohammed bin Salman introduced new freedoms for women. While women are now permitted to travel alone or travel abroad without their male guardian’s consent, their rights remain restricted. The ‘religious police’ continues to harass them. Women are still required to limit the time they spend with men not related to them and a large portion of public buildings such as offices, banks and universities still have separate entrances. To aggravate matters, women are not allowed to try on clothes in changing stalls while shopping.

All of this is happening today, in 2021.

Equality and freedom

Under President Nelson Mandela’s leadership, the country’s foreign policy was characterized by human rights; the new Constitution a beacon of equality. The government was committed towards a human-rights based foreign policy and expressed solidarity with those oppressed abroad. Can South Africa truly practice a human-rights based foreign policy and have such friends? I dare argue not.