Part 3 excerpt

A recent paper by Justin Hastings, Daniel Wertz, and Andrew Yeo and published by the Washington-based National Committee on North Korea, entitled ‘Market Activities & the Building Blocks of Civil Society in North Korea’. In broad brushstrokes, it probes the notion that markets are building networks and relationships of trust and cooperation – this would be a modest start to fostering a civil society. This would still be at a considerable remove from the robust civil societies that articulate demands and counterbalance state power in democracies, but it would be a start.

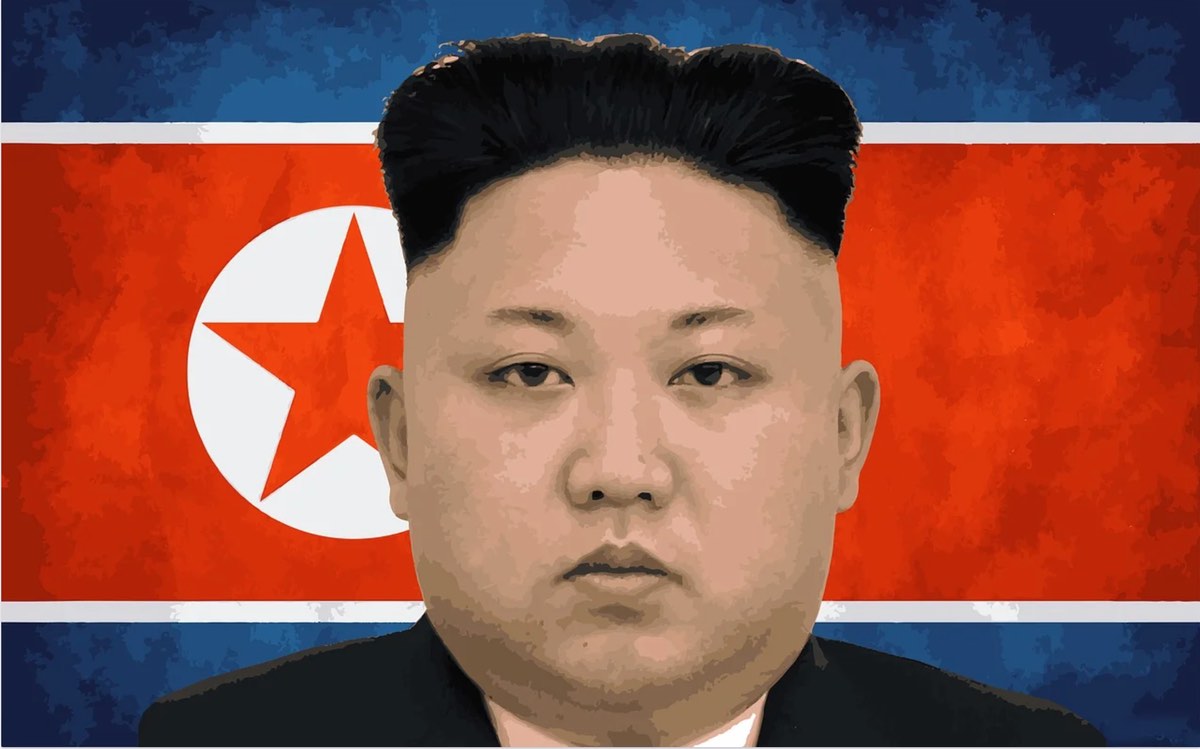

Equally, the posture of the North Korean regime seems unbending. At the 8th Congress of the Korean Workers Party, held in January this year, Kim Jong-un stated ‘the most brilliant achievement achieved in the last five years…is the extraordinarily expanded and strengthened political and ideological power’. The congress affirmed the centrality of statist thinking in its economics, with Kim urging that economic questions should be dealt with from a fundamentally political point of view. The primacy of its military in its worldview (and also, within the Songbun milieu, as a coveted avenue of personal status and security for its members) seems undiminished. The congress heard plans for the expansion of its weapons systems (this after having a few years ago lauded achieving nuclear weapons status as a major achievement). It would be ‘foolish and dangerous’, he said, not to maintain the military emphasis in the face of external threats.

Thus, accounts from defectors suggest that there exists a genuine loyalty on the part of the population. A survey of defectors by the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies in South Korea found not only that most felt that a majority of North Koreans supported their government, but that a large majority of defectors continued to feel a sense of pride in Juche. Darren Zook likewise says that his experience with defectors often reveals a deep ambivalence about their actions and whether leaving North Korea was the ethically correct decision.

Zook says he is not optimistic about the prospects for reform. What has been allowed to take place has been as closely controlled as possible. There is simply no equivalent in North Korea to the East Germans who could tune into West German news, the Poles who could draw inspiration from Catholicism, or the Hungarians or Yugoslavs who could banter with Western tourists, or even Chinese entrepreneurs trading with foreign markets. In his analysis, Songbun – arguably the centrepiece of its brand of repression – has become somewhat more important in recent years, and it may be Kim Jong-un’s enduring intellectual legacy to enshrine this is a future iteration of the country’ constitution.

Reform, should it come, would need to originate from within the state, at least as a first step. To the extent that some reformist impulses exist, Zook argues, they would have to be articulated as measures calculated to strengthen and fortify the existing system. He adds that the best prospect for doing this might be Kim Jong-un’s sister Kim Yo-jong. At times touted as an heir apparent, Zook describes her as ‘someone to watch’. For the perceptive observer, cultural cues imply that she holds an especial degree of status in the system, and appears to believe that the country’s overall economic retardation is a significant problem for it. On the other hand, any reform push would be met with dogged resistance, and whether she could carry it – not least, because she is a woman – is open to question.

Where the national meets the international, and the future is over the horizon

Successive US administrations have been concerned about a militaristic, nuclear-armed North Korea – so perhaps it may seem churlish to take note of idiosyncratic rules around hair and clothing.

The reality, though, is that for North Korea, the two are inextricably linked. Its refusal to bow to pressure or even to concede to what most of the world would be regarded as the dictates of sober reality is built within its worldview. Belligerence on the world stage, the stop-me-if-you-dare diplomacy cannot be disentangled from its determination to maintain its unique social and political order. To abandon or substantially modify any part of this would be to betray what is of fundamental importance to its leadership.

Mullets, in a sense, are as important to understanding North Korea as nukes. And their banning is perhaps more emblematic of why no reform is on the way than its military programmes.

So, when a senior official at Human Rights Watch calls on the world to ‘act’ – ‘Kim Jong-un isn’t going to change his behaviour unless concerned countries demand it’ – his frame of reference is at odd with reality and his call to action invariably pointless.

What does all this mean? North Korea defies comparison with pretty much any other society. Putting aside considerations of whether it constitutes a threat to its neighbours or the world, it poses a difficult set of moral issues to those who are repelled at the operation of the North Korean state and its internal arrangements. Simply put there is very little that can be done, short of a military intervention that should best be avoided.

For South Africans, North Korea is distant and almost an abstraction. South Africa has no resident embassy there, but maintains one in South Korea. North Korea is sometimes rolled out as the object of anti-imperialist solidarity, generally by the most ideologically rigid and intellectually bereft corners of South African politics. (The ANC Youth League issued a statement on Kim Jong-Il’s death which praised him for having ‘managed an economy that saved people from joblessness, homelessness, illiteracy or lack of education thereof, and the varying degrees of poverty’, damned South Korea as ‘the creation of imperialism’, its president as a ‘traitor’, and lauded the ‘air steriliser’ that Kim had supposedly invented to combat climate change. All with indifferent grammar.) Opposing this sort of nonsense is perhaps one of the few avenues available to challenge North Korea – but again, at such a remove from any prospect of impact that one might ask whether doing so has much point.

Ultimately, there is probably little to be done, but to wait, to watch and to be aware that North Korea is a genuine experience for millions of people, akin somewhat to what another Briton said, this time of Africa: ‘the state of Africa is a scar on the conscience of the world.’ Yet Tony Blair’s famous injunction was a call for the world to take action in a way that is not possible in respect of North Korea.

The last word goes to Barbara Demick, concluding her 2010 book on North Korea, Nothing to Envy: Real Lives in North Korea. Noted by many travellers to the country is the fact that North Koreans often sit, not rushing about carrying out the routines and duties of daily life, with the frenetic energy associated with Asia, or for that matter most of the world, ‘they stare straight ahead as though they are waiting – for a tram, maybe, or a passing car? A friend or a relative? Maybe they are waiting for nothing in particular, just waiting for something to change.’